Emerging research is sparking change in the future of MS management

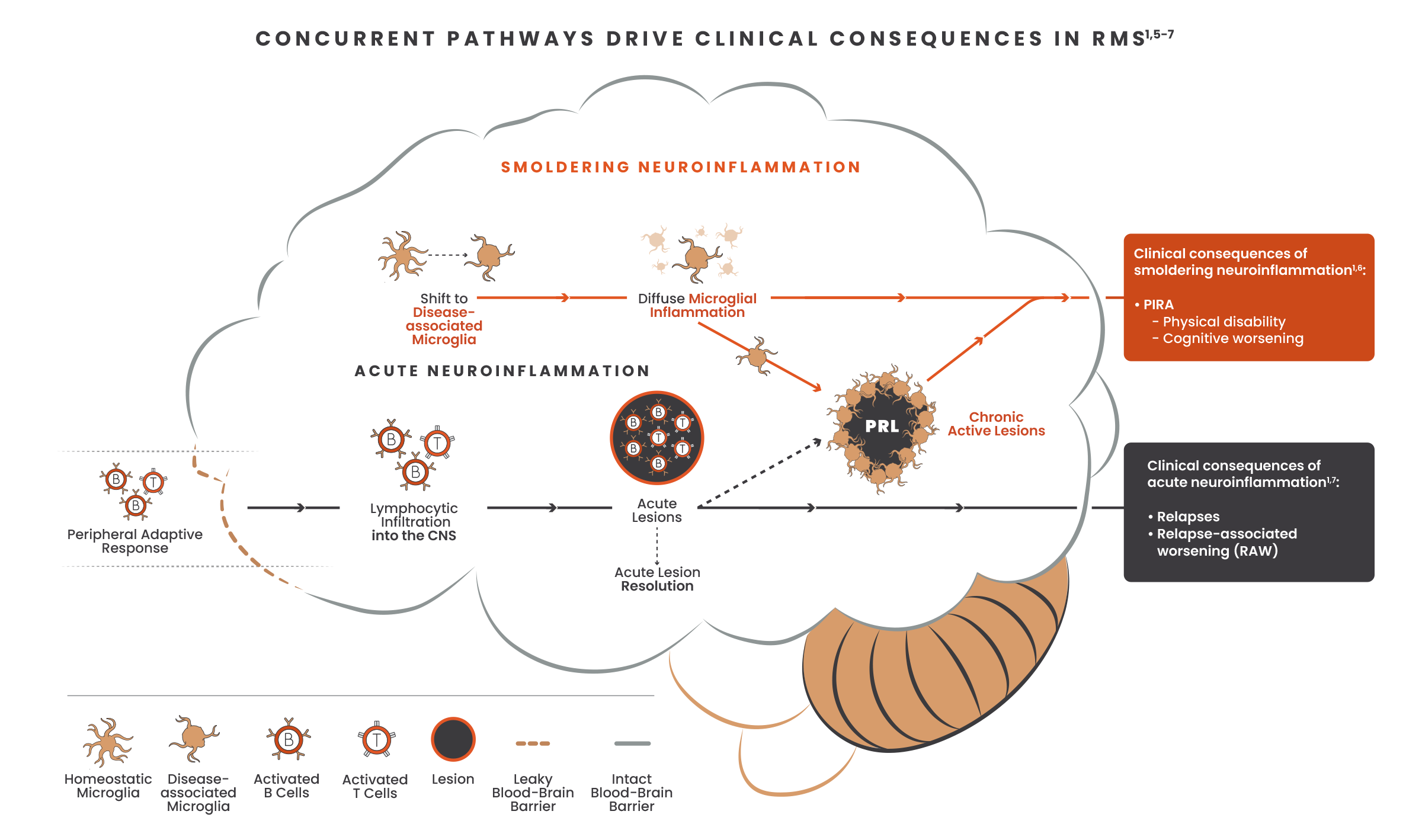

Optimal MS care includes a comprehensive approach that addresses both acute and smoldering neuroinflammation throughout the course of a patient’s disease.1,2

Both acute and smoldering neuroinflammation may occur from disease onset. Addressing both processes early on could help prevent disease progression and impact long-term disability outcomes in patients with MS.1,3,4

Occurring exclusively in the CNS, smoldering neuroinflammation has been largely inaccessible due to the lack of treatments that directly target disease-associated microglia and cross the blood-brain barrier.1,7,8

Cross the blood-brain barrier

Target disease‑associated microglia

One way to impact smoldering neuroinflammation is to cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on microglia to reduce neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative processes.8

Given the significant unmet need to effectively address disability accumulation, the next generation of DMTs should impact the main driver of disability: smoldering neuroinflammation.1,9,10

Hear from the experts

Celia Oreja-Guevara, MD, PhD, discusses the underlying biology of acute and smoldering neuroinflammation at EAN 2023

Smoldering Stories

Hear how smoldering neuroinflammation impacted the lives of patients with MS

References:

-

Giovannoni G, Popescu V, Wuerfel J, et al. Smouldering multiple sclerosis: the ‘real MS’. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2022;15:17562864211066751. doi:10.1177/17562864211066751

-

Cree BAC, Hollenbach JA, Bove R, et al; University of California, San Francisco MS-Epic Team. Silent progression in disease activity-free relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2019;85(5):653-666.

-

Simpson A, Mowry EM, Newsome SD. Early aggressive treatment approaches for multiple sclerosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2021;23:19. doi:10.1007/s11940-021-00677-1

-

Scalfari A. MS can be considered a primary progressive disease in all cases, but some patients have superimposed relapses - Yes. Mult Scler. 2021;27(7):1002-1004.

-

Yong VW. Microglia in multiple sclerosis: protectors turn destroyers. Neuron. 2022;110(21):3534-3548.

-

Kuhlmann T, Moccia M, Coetzee T, et al. Multiple sclerosis progression: time for a new mechanism-driven framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(1):78-88.

-

Häusser-Kinzel S, Weber MS. The role of B cells and antibodies in multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, and related disorders. Front Immunol. 2019;10:201. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00201

-

Correale J, Halfon MJ, Jack D, Rubstein A, Villa A. Acting centrally or peripherally: a renewed interest in the central nervous system penetration of disease-modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;56:103264. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2021.103264

-

Geladaris A, Torke S, Weber MS. Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase inhibitors in multiple sclerosis: pioneering the path towards treatment of progression? CNS Drugs. 2022;36(10):1019-1030.

-

Absinta M, Lassmann H, Trapp BD. Mechanisms underlying progression in multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33(3):277-285.